The repackaging of post-vaccination measles

Following introduction of the measles vaccine, there have been several outbreaks of diseases "clinically similar" to measles, raising questions about the efficacy of the measles vaccine

Table of Contents

Supplement 1 - Kawasaki Disease (KD) and Measles

Supplement 2 - Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) and Measles

Supplement 3 - Hand-foot-and-mouth-disease (HFMD) and Measles

Supplement 4 - Atypical Measles

Summary

While measles death rate in US had declined by 98% and survival rate was estimated at 99.98% in UK, before the introduction of the measles vaccine, proponents of the measles vaccine often argue that the measles vaccine was effective in bringing down the incidence of measles, quoting CDC’s data. [1, 2, 3]

However, a closer scrutiny of publicly available data about the prevalence of exanthematous diseases, clinically similar to measles, before and after the introduction of measles vaccine (and indeed other vaccines in some cases), leaves the above claim of a declining incidence post measles vaccine introduction on a very shaky ground.

In another writeup, I have argued how true vaccine efficacy is grossly overstated often by redefinition of the so called ‘vaccine preventable disease’, and introduction of new terminologies or ‘discovery’ of new diseases attributed to a ‘novel pathogen’. This is true of virtually every single so-called ‘vaccine preventable disease’ such as polio, smallpox, Japanese Encephalitis etc. [4]

It is important to understand that many of the so called vaccine preventable diseases used to be diagnosed clinically prior to the introduction of vaccines, but following the introduction of vaccines, gradually, laboratory diagnosis took over and clinically compatible diseases were diagnosed as something else, and for the most part, attributed to other viruses or designated as having an unknown etiological agent.[5, 6, 7]

In this writeup, we drill down further on measles, and specifically talk about the below 4 conditions, which, when looked at in totality, raise severe doubts about any efficacy whatsoever of the measles vaccine. These include

Atypical Measles: This terminology was attributed to recipients who had previously received the measles vaccine, both killed virus vaccine and live virus vaccine. It led to the eventual discontinuation of the killed measles virus vaccine.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF): This is another disease clinically similar to measles. It had declined significantly before the introduction of the measles vaccine. However, after the introduction of the measles vaccine, its incidence increased significantly, raising questions of whether vaccinated individuals with measles were being misdiagnosed as RMSF.

Kawasaki Disease (KD): Kawasaki disease was a new disease that was discovered after the trial and introduction of the measles vaccine in Japan, and its incidence increased significantly after the measles vaccine was made mandatory in Japan. Its incidence is not tracked in North America, but studies have indicated an increasing incidence as well as the possibility of measles being misdiagnosed as KD.

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD): HFMD is another disease that’s clinically similar to measles. While its incidence had not been actively tracked historically, recent data indicates an increased incidence, particularly in children under the age of 5, raising questions of the impact of vaccines or immunization schedule.

There are other diseases that are clinically similar to measles, however their incidence data is hard to come by. Hence this writeup focuses on the above 4, to demonstrate the illusion of reduced incidence of measles post introduction of the measles vaccine.

Eventually, if true efficacy of the measles vaccine is to be deduced, and it’s epidemiological impact be studied, then any surveillance system should track 2 things : (1) the incidence of all acute exanthematous diseases clinically similar to measles, before and after introduction of the measles vaccine, and (2) the prevalence of acute exanthematous diseases in vaccinated versus unvaccinated cohorts.

Supplement 1: Kawasaki Disease (KD) and Measles

“Kawasaki Disease: A Measles cover up?”

“ The continuing endemicity of measles in countries where Kawasaki disease is not seen and the increasing recognition of Kawasaki disease as the measles rate has declined suggest that measles has masked Kawasaki disease until very recently in developed countries and continues to obscure the diagnosis in many other parts of the world." [8]

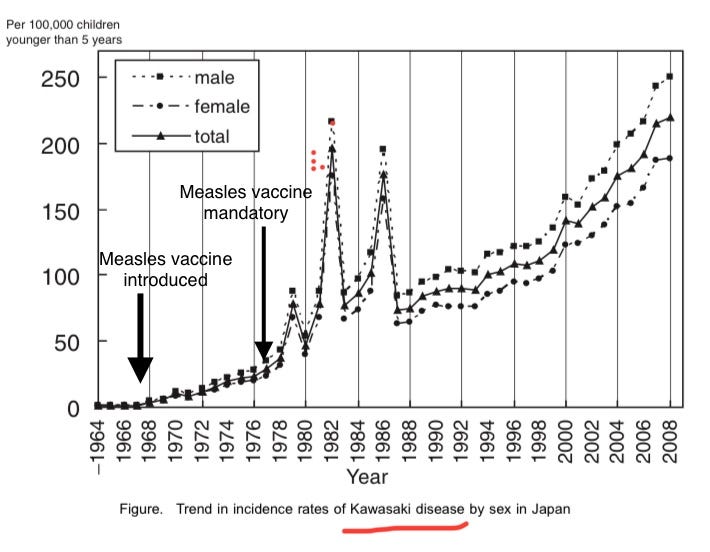

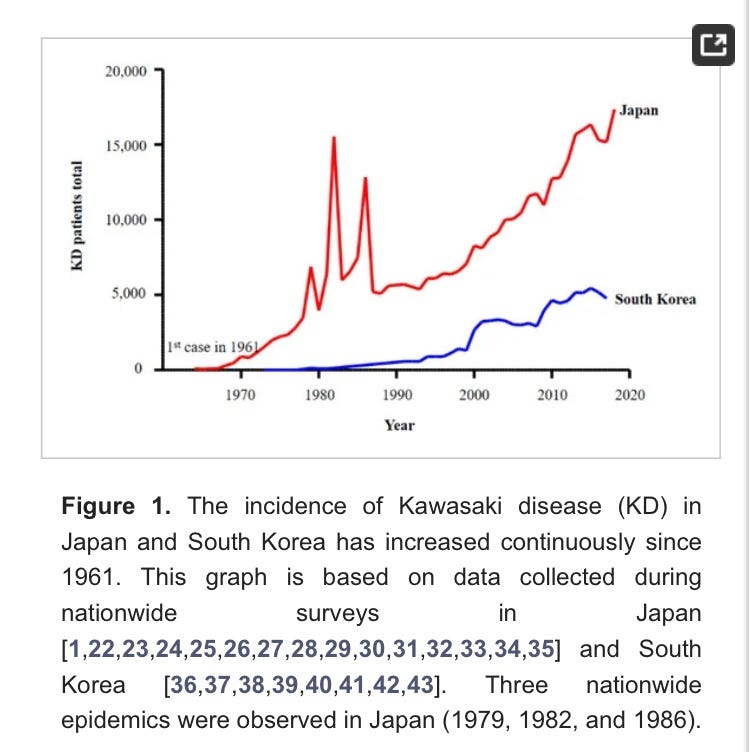

Kawasaki disease was discovered in Japan around the same time the measles vaccines were trialled & introduced & incidence increased significantly once the vaccine was made mandatory. [9, 10, 11]

“Difficult to differentiate Kawasaki disease from measles on clinical grounds alone.” [12]

“Measles mimics Kawasaki Disease. Measles and Kawasaki Disease may be associated.” [13]

“Cases of measles have been misdiagnosed as Kawasaki Disease.” [14]

Incidence of Kawasaki disease sharply increased in South Korea after measles vaccines were made mandatory in 1985 [15, 16]

Kawasaki incidence in Ontario from 1995 to 2017 showed a steady increase. [17]

“This case highlights the potential role of measles virus in triggering Kawasaki disease” [18]

“The differential diagnosis of atypical measles includes Kawasaki disease” [19]

Case report of a 14 year old.

Diagnosis: Measles related Kawasaki syndrome or atypical measles mimicking Kawasaki syndrome [20]

US: Kawasaki disease hospitalizations almost doubled from 1988 to 1997 (representative data from 900 hospitals in 22 states) [21]

India: “Kawasaki disease was rarely reported till the mid 90s” i.e it started getting more frequently reported only after the introduction of the measles vaccine (licensed in 1985, added to immunization schedule in 1990) [22, 23]

“Some cases of Mucocutaneous Lymph Node Syndrome (i.e. Kawasaki Disease) may be misdiagnosed as Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF)”. [24]

8 month old infant suspected of having measles was diagnosed with Kawasaki disease. [25]

South Africa: A child initially diagnosed as measles was re-diagnosed as Kawasaki disease . [26]

Supplement 2: Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) and Measles

“Several patients diagnosed having RMSF were subsequently proven to have measles. These patients had received killed measles vaccine in the past”. [27]

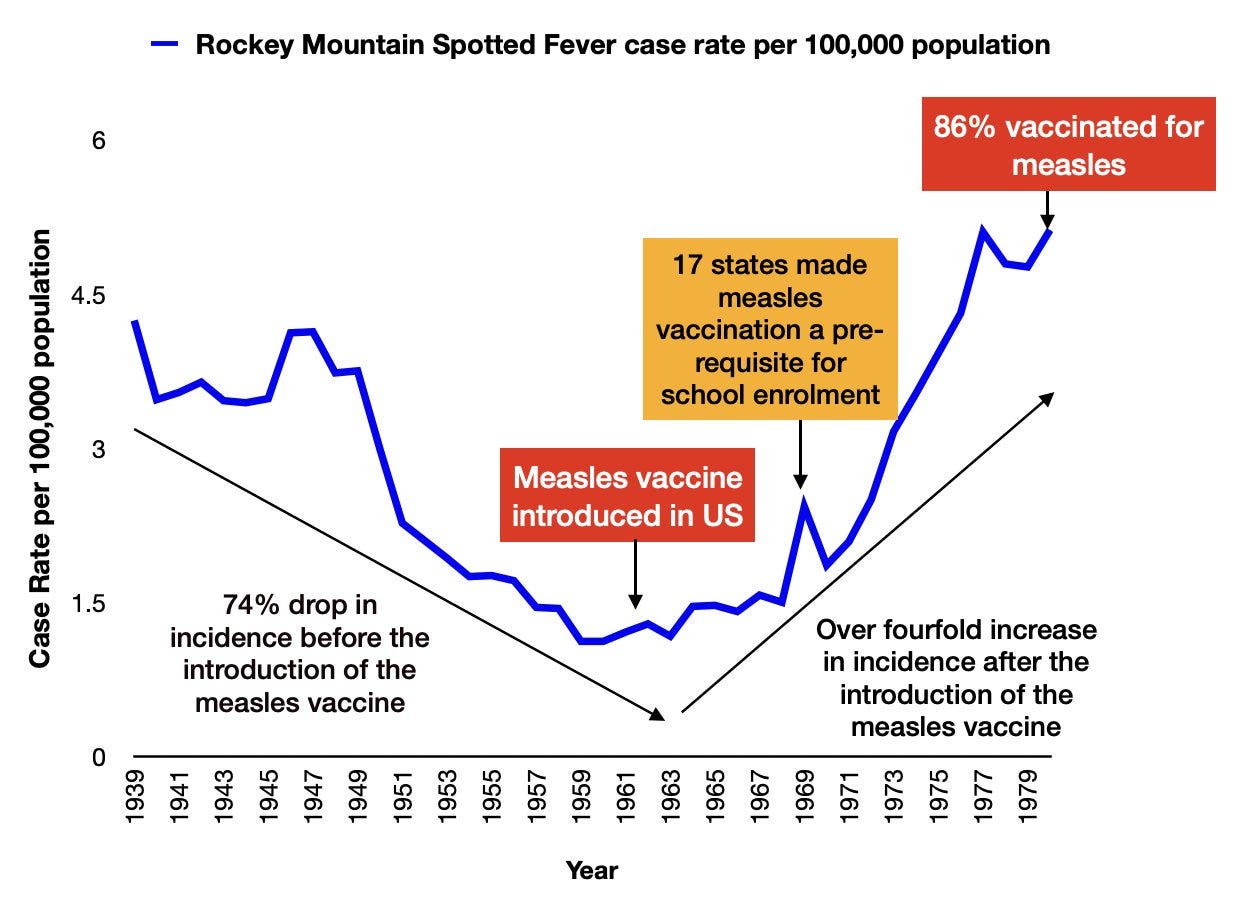

Prior to the introduction of the measles vaccine, RMSF (the most common form of rickettsioses or spotted fever in US) had declined by 74% since 1939. However, after the introduction of the measles vaccine, RMSF incidence increased over fourfold over the next 17 years. [28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34]

As RMSF incidence increased over fourfold 17 years after the introduction of the measles , despite voluntary reporting, CDC redefined its diagnosis using stricter criteria likely understating incidence post-1980 by ~50%. Plotted below is the RMSF incidence with and without change in CDC’s definition. The 1980 change in diagnostic criteria coincided with introduction of requiring measles vaccination for school enrolment in 50 states. [28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34]

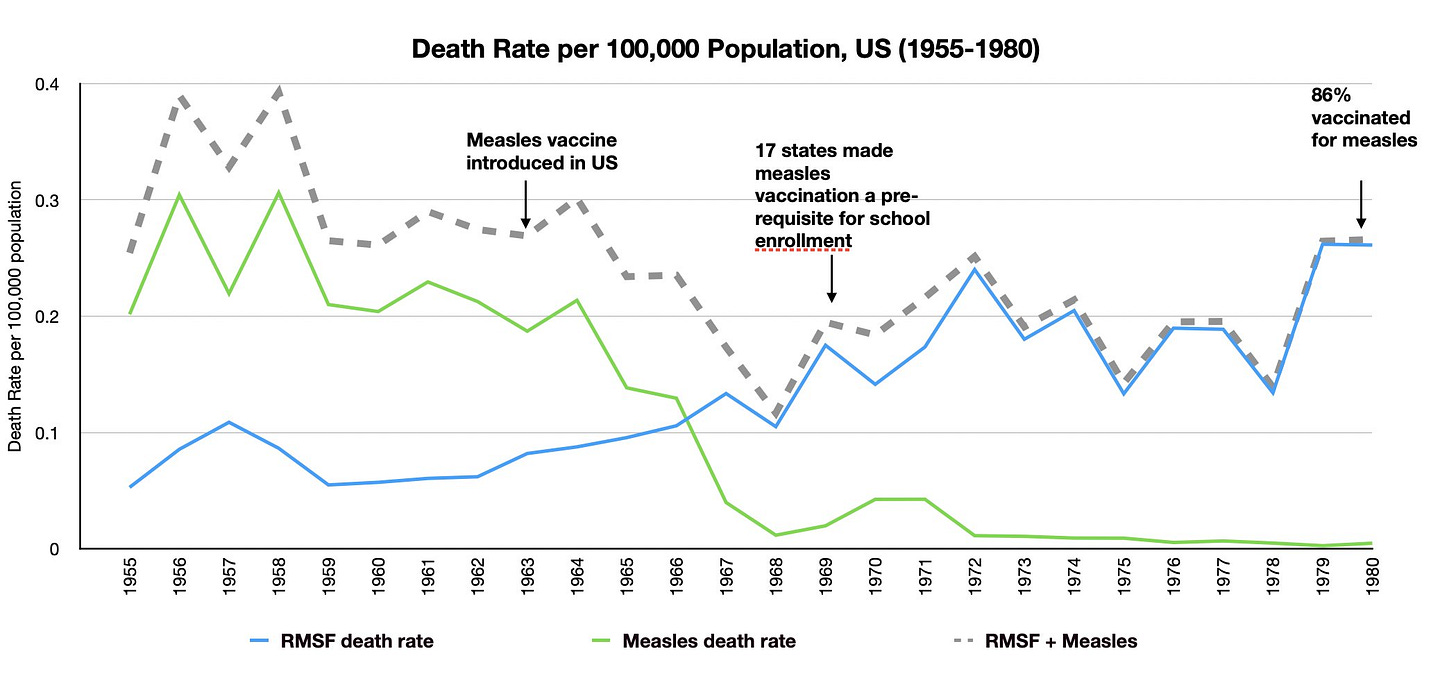

Plotted below are RMSF deaths vs. measles deaths since the introduction of the measles vaccine. There was hardly any change in the combined fatality rate of these 2 diseases after the introduction of the vaccine. [29, 35]

Italy - Spotted fever incidence (rickettsioses) increased significantly after measles vaccine was made available in 1976. [36, 37]

“Vaccinees developed atypical measles, which resembles Rocky Mountain spotted fever”. [38]

A patient diagnosed as RMSF was rediagnosed as atypical measles after confirming history of killed measles vaccination. [39]

“The rash may suggest Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever but lead to diagnosis of atypical measles following serologic examination”. [40]

"Rocky Mountain spotted fever is sometimes confused with typhoid, measles, scarlet fever, smallpox, postmeasles encephalitis, purpura haemorrhagica, epidemic cerebrospinal meningitis, secondary syphilis, Colorado tick fever and endemic typhus." …”The diseases most commonly causing confusion are typhoid, severe measles, smallpox, epidemic meningitis , ....typhus fever” [41, 42]

“After the eruption has evolved, Rocky Mountain spotted fever may have to be distinguished from such diseases as meningococcemia, typhoid, endemic typhus, measles, and dermatitis medicamentosa.” [43]

“Measles can be confused with RMSF due to rash and respiratory symptoms” [44]

“Atypical measles rash mimicking Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever” [45]

Supplement 3: Hand-foot-mouth- disease (HFMD) and Measles

“Hand-foot-and-mouth disease has similar manifestations to measles and is easy to misdiagnose” [46]

“HFMD should be differentiated from other exanthemata seen in childhood….including atypical measles”. [47]

“Measles may be mistaken for HFMD in an outbreak setting” [48]

Case Report: Hand-foot-and-mouth disease resembling measles. [49]

“Measles is sometimes misdiagnosed as hand-foot-and-mouth disease” [50]

“The foot-and-mouth-disease virus may also be a contaminant of vaccine employed for jennerian (i.e. smallpox) vaccination.” [51]

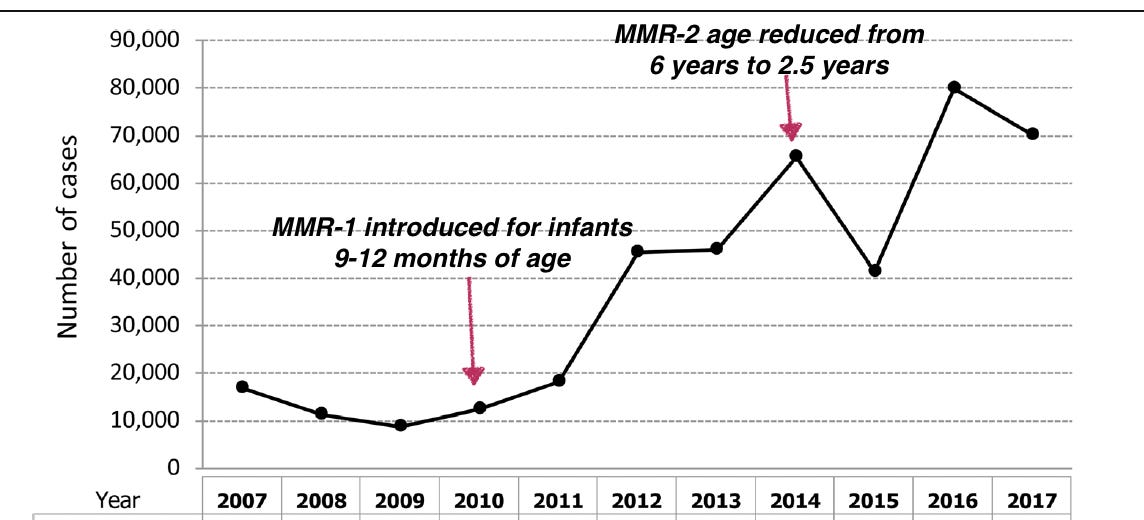

HFMD in Thailand occurs predominantly in children 1-2 years of age. 89% of the cases are in children 5 years and under. This brings into question the impact of the vaccination schedule on HFMD as the incidence has increased significantly as more vaccines/doses kept getting added to the immunization schedule. [52, 53, 54]

In China, HFMD incidence increased significantly following the introduction of JE vaccine in 2007. In 2014, HFMD cases were up fivefold compared to 2008, resulting in the introduction of the HFMD vaccine in December, 2015. [55, 56]

Japan experienced it’s first outbreak of HFMD just 3 years after the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1969. Just 2 years after the vaccine was made compulsory, Japan experienced its largest outbreak of HFMD until then, with over 36,000 reported cases (actual incidence was likely 10 times higher per the report). In short, following the introduction of the measles vaccine, Japan experienced several outbreaks of “measles like illnesses”, namely Kawasaki disease and Hand-foot-and-mouth disease. [57, 58]

Supplement 4: Atypical Measles

“Atypical measles can be mistaken for several other diseases such as Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Kawasaki disease etc.” [59]

Atypical measles is measles in those who were previously vaccinated for measles - either killed virus vaccine, or live virus vaccine, or multiple doses involving both these types of vaccines. [60, 61]

5 out of 10 children with atypical measles were diagnosed as some other disease. [62]

This study highlighted that atypical measles was correctly diagnosed in only 17 out of 56 cases, another example pointing to an artificially reduced incidence of measles due to misdiagnosis, after the introduction of the measles vaccine. [63]

“Atypical measles may be misdiagnosed as varicella, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, toxic shock syndrome, or drug eruption.” [64]

Recommendation

Given the different types of exanthematous diseases that measles may be confounded with, the high likelihood of misdiagnosis in a vaccinated person, the correct scientific approach would be to track prevalence of all exanthematous diseases before and after vaccination, measuring the overall burden of all exanthematous diseases on the target population. Additionally, the prevalence of these acute exanthematous diseases should be recorded and compared between vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts. This will uncover any misleading ‘vaccine efficacy’ driven by widespread misdiagnosis. [65]

References

[1] Sinclair, Ian. Vaccination: The Hidden Facts. 1992, URL: https://ia601707.us.archive.org/2/items/sinclair-ian-vaccination-the-hidden- facts_202012/Sinclair%20Ian%20-%20Vaccination%20The%20hidden%20facts.pdf

[2] Warin, J. F. (1967). Routine Measles Vaccination as a Community Health Measure. Royal Society of Health Journal, 87(5), 261–266.doi:10.1177/146642406708700510

https://sci-hub.se/https://doi.org/10.1177/146642406708700510

[3] CDC. “Measles Cases and Outbreaks.” Measles (Rubeola), 13 May 2024, www.cdc.gov/measles/data-research/.

[4]Srivastava, Vratesh. “Smallpox - Eradicated or Renamed?” Substack.com, Vratesh’s Newsletter, 3 Sept. 2024, vratesh.substack.com/p/smallpox-eradicated-or-renamed.

[5] Srivastava, Vratesh. “Chandipura Virus: Media Confirms “Outbreak” Based on 1 Confirmed Case.” Substack.com, Vratesh’s Newsletter, 19 July 2024, vratesh.substack.com/p/chandipura-virus-media-confirms-outbreak.

[6] Srivastava, Vratesh. “Encephalitis in India: A Man Made Epidemic?” Vratesh’s Newsletter, 31 Mar. 2024, vratesh.substack.com/p/encephalitis-in-india-a-man-made.

[7] Srivastava, Vratesh. “The Other Side of India’s Polio Eradication Story.” Vratesh’s Newsletter, 18 Nov. 2023, vratesh.substack.com/p/the-other-side-of-indias-polio-eradication.

[8] Rowe, R D, et al. “Kawasaki Disease: A Measles Cover-Up?” CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal, vol. 136, no. 11, June 1987, p. 1146, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1492163/pdf/cmaj00143-0012.pdf.

[9]Uehara, Ritei, and Ermias D. Belay. “Epidemiology of Kawasaki Disease in Asia, Europe, and the United States.” Journal of Epidemiology, vol. 22, no. 2, 2012, pp. 79–85, https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.je20110131. Epidemiology of Kawasaki Disease in Asia, Europe, and the United States (jst.go.jp)

[10] Nakano, Takashi. “Changes in Vaccination Administration in Japan.” Vaccine, vol. 41, no. 16, 16 Mar. 2023, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X23002827, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.03.020. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264410X23002827.

[11] Munehiro Hirayama. “Measles Vaccines Used in Japan.” Reviews of Infectious Diseases, vol. 5, no. 3, 1983, pp. 495–503. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4453064.

[12] MAKHENE, MAMODIKOE K. MD; DIAZ, PAMELA S. MD. Clinical presentations and complications of suspected measles in hospitalized children. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 12(10):p 836-839, October 1993. https://dacemirror.sci-hub.se/journal-article/dacd768a542c668ab7e43da895a10f37/makhene1993.pdf?download=true .

[13] Manel Hsairi, et al. “A Febrile Skin Rash May Hide Another.” European Journal of Basic Medical Sciences, vol. 9, no. 1, 21 June 2019, pp. 1–4, www.ejbms.net/article/a-febrile-skin-rash-may-hide-another-10815, https://doi.org/10.21601/ejbms/10815. https://www.ejbms.net/download/a-febrile-skin-rash-may-hide-another-10815.pdf.

[14] Dajani, A S, et al. “Diagnosis and Therapy of Kawasaki Disease in Children.” Circulation, vol. 87, no. 5, May 1993, pp. 1776–1780, https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.87.5.1776. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1161/01.CIR.87.5.1776

[15] Lee, Jong-Keuk. “Hygiene Hypothesis as the Etiology of Kawasaki Disease: Dysregulation of Early B Cell Development.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 22, no. 22, 15 Nov. 2021, p. 12334, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8622879/, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222212334. https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/22/22/12334.

[16] Seok, Hyeri, et al. “Report of the Korean Society of Infectious Diseases Roundtable Discussion on Responses to the Measles Outbreaks in Korea in 2019.” Infection and Chemotherapy, vol. 53, no. 3, 1 Jan. 2021, pp. 405–405, https://doi.org/10.3947/ic.2021.0084. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8511360/#:~:text=The%20first%20live%2Dvirus%20measles,in%20March%201970%20%5B1%5D

[17] Robinson, Cal, et al. “Incidence and Short-Term Outcomes of Kawasaki Disease.” Pediatric Research, vol. 90, no. 3, 1 Sept. 2021, pp. 670–677, www.nature.com/articles/s41390-021-01496-5, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01496-5.

[18] Mojgan Faraji-Goodarzi, et al. “Kawasaki Disease Triggered by Measles: A Case Report and Review of the Literature.” Authorea (Authorea), 1 Sept. 2024, https://doi.org/10.22541/au.172521044.42570278/v1, https://d197for5662m48.cloudfront.net/documents/publicationstatus/221701/preprint_pdf/f9104cce94f1b03a860e15aa064dc446.pdf

[19] Nichols, Karen J. “Atypical Measles: A Diagnostic Conundrum.” The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, vol. 90, no. 7, 1 July 1991, pp. 691–694, https://doi.org/10.1515/jom-1991-900713, https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/jom-1991-900713/html

[20] Martin, L et al. “Kawasaki syndrome or atypical measles mimicking Kawasaki syndrome?.” Acta dermato-venereologica vol. 77,4 (1997): 329. doi:10.2340/0001555577329, https://www.medicaljournals.se/acta/content_files/files/pdf/77/4/77329.pdf

[21]Chang, R.-K. R. “Hospitalizations for Kawasaki Disease among Children in the United States, 1988-1997.” PEDIATRICS, vol. 109, no. 6, 1 June 2002, pp. e87–e87, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.109.6.e87, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/11329804_Hospitalizations_for_Kawasaki_Disease_Among_Children_in_the_United_States_1988-1997

[22] John, T Jacob, and Valsan P Verghese. “Time to Re-Think Measles Vaccination Schedule in India.” The Indian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 134, no. 3, Sept. 2011, p. 256, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3193705/.

[23] Singh, Surjit. “Kawasaki Disease in India � Lessons Learnt over the Last 20 Years.” Indianpediatrics.net, Indian Pediatrics, 2016, 53: 119-124.

www.indianpediatrics.net/feb2016/feb-119-124.htm.

[24] Bergeson, Paul S. “Mucocutaneous Lymph Node Syndrome.” JAMA, vol. 237, no. 21, 23 May 1977, p. 2299, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1977.03270480039017, https://sci-hub.se/10.1001/jama.1977.03270480039017

[25] Bernhardt, I B. “Mucocutaneous Lymph Node Syndrome with Encephalopathy in the Continental United States.” Western Journal of Medicine, vol. 125, no. 3, Sept. 1976, p. 230, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1237287/, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1237287/pdf/westjmed00277-0074.pdf

[26] P. L. VAN DER MERWE, et al. “Mucocutaneous Llymph Node Syndrome (Kawasaki Disease), a Report of 2 Cases.” SA MEDIESE TYDSKRIF, 20 Dec. 1980, pp. 1014–1016, journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/AJA20785135_11790

[27] Linnemann, C C Jr, and P J Janson. “The clinical presentations of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Comments on recognition and management based on a study of 63 patients.” Clinical pediatrics vol. 17,9 (1978): 673-9. doi:10.1177/000992287801700901, https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=14c5a20e7ceb51b4ce65f775de9a6185257458ed

[28] Bernard, Kenneth W, et al. “Surveillance of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever in the United States, 19781980.” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 146, no. 2, 1982, pp. 297–299. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/30109626, https://doi.org/10.2307/30109626.

[29] CDC. “Data and Statistics on Spotted Fever Rickettsiosis.” Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF), 20 May 2024, www.cdc.gov/rocky-mountain-spotted-fever/data-research/facts-stats/index.html.

[30] Wilfert, Catherine M, et al. “Epidemiology of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever as Determined by Active Surveillance.” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 150, no. 4, 1 Oct. 1984, pp. 469–479, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/150.4.469, https://sci-hub.se/10.1093/infdis/150.4.469

[31] WHO. Weekly Epidemic Report No. 47. World Health Organisation, 27 Nov. 1981, iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/223745/WER5647_373-373.PDF.

[32] Conis, Elena. “Measles and the Modern History of Vaccination.” Public Health Reports, vol. 134, no. 2, 14 Feb. 2019, pp. 118–125, https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354919826558.

[33] World Health Organization, “WHO Immunization Data Portal - Detail Page.” Immunization Data, immunizationdata.who.int/global/wiise-detail-page/measles-vaccination-coverage.

[34] Hinman, Alan R. “The Opportunity and Obligation to Eliminate Measles from the United States.” JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 242, no. 11, 14 Sept. 1979, p. 1157, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1979.03300110029022, https://sci-hub.se/10.1001/jama.1979.03300110029022

[35] CDC. “ Reported Cases and Deaths from Vaccine Preventable Diseases, United States, 1950-2013.” Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases, 13th Edition , CDC, web.archive.org/web/20150905212143/www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/appendices/e/reported-cases.pdf.

[36] European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. “Vaccine Scheduler | ECDC.” Vaccine-Schedule.ecdc.europa.eu, vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu/Scheduler/ByCountry?SelectedCountryId=103&IncludeChildAgeGroup=true&IncludeChildAgeGroup=false&IncludeAdultAgeGroup=true&IncludeAdultAgeGroup=falseLast.

[37] Rovery, Clarisse, et al. “Questions on Mediterranean Spotted Fever a Century after Its Discovery.” Emerging Infectious Diseases, vol. 14, no. 9, Sept. 2008, pp. 1360–1367, https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1409.071133, https://www.semanticscholar.org/reader/4ec1cec333a12ea0d15820d51193ad765cd33015

[38] Brentjens, M. H., Yeung-Yue, K. A., Lee, P. C., & Tyring, S. K. (2003). Vaccines for viral diseases with dermatologic manifestations. Dermatologic Clinics, 21(2), 349–369.doi:10.1016/s0733-8635(02)00098-0, https://sci-hub.se/10.1016/S0733-8635(02)00098-0

[39] HALL, WILLIAM J. “Atypical Measles in Adolescents: Evaluation of Clinical and Pulmonary Function.” Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 90, no. 6, 1 June 1979, p. 882, https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-90-6-882, https://2024.sci-hub.se/4131/a471d9ecaf9942f1cfc95bcd27f40803/haas1976.pdf?download=true

[40] Henderson, J A, and D I Hammond. “Delayed Diagnosis in Atypical Measles Syndrome.” Canadian Medical Association Journal, vol. 133, no. 3, Aug. 1985, p. 211, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/instance/1346153/pdf/canmedaj00266-0053.pdf.

[41] PARKER, R. R. “ROCKY MOUNTAIN SPOTTED FEVER.” Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 110, no. 16, 16 Apr. 1938, p. 1273, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1938.62790160008009, sci-hub.se/10.1001/jama.1938.62790160008009

[42] Baker, George E. “ROCKY MOUNTAIN SPOTTED FEVER.” Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 122, no. 13, 24 July 1943, pp. 841–841, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1943.02840300001001, https://sci-hub.se/10.1001/jama.1943.02840300001001

[43] Cawley, Edward P. “ROCKY MOUNTAIN SPOTTED FEVER.” Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 163, no. 12, 23 Mar. 1957, p. 1003, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1957.02970470001001.

[44] Crutcher, John S. “ROCKY MOUNTAIN SPOTTED FEVER.” Southern Medical Journal, vol. 26, no. 5, May 1933, pp. 415–417, https://doi.org/10.1097/00007611-193305000-00007.

[45] Horwitz, M S, et al. “Atypical Measles Rash Mimicking Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 289, no. 22, 29 Nov. 1973, pp. 1203–1204, https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm197311292892223.

[46] Yan, Xiang et al. “Clinical and Etiological Characteristics of Atypical Hand-Foot-and-Mouth Disease in Children from Chongqing, China: A Retrospective Study.” BioMed research internationalvol. 2015 (2015): 802046. doi:10.1155/2015/802046

[47] Li, Xing-Wang, et al. “Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease (2018 Edition).” World Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 14, no. 5, Oct. 2018, pp. 437–447, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-018-0189-8.

[48] Shah, V A et al. “Clinical characteristics of an outbreak of hand, foot and mouth disease in Singapore.” Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore vol. 32,3 (2003): 381-7.

[49] Gohd, Robert S., and Harris C. Faigel. “HAND-FOOT-AND-MOUTH-DISEASE RESEMBLING MEASLES a LIFE-THREATENING DISEASE: CASE REPORT.” Pediatrics, vol. 37, no. 4, 1 Apr. 1966, pp. 644–648, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.37.4.644.

[50] The Global Medical misDiagnosis Database. “Measles Diagnosis - Hand Foot and Mouth Disease Misdiagnosis.” Mymisdiagnosis.com, 2022, www.mymisdiagnosis.com/misdiagnosis/hand-foot-and-mouth-disease/711.

[51] LEVIN, S et al. “Hand-foot-and-mouth disease.” South African medical journal = Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde vol. 36 (1962): 502-4, https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/AJA20785135_40356

[52] World Health Organization Regional Office for South East Asia. FACTSHEET 2020 Thailand - EPI. 2020, iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/336764/tha-epi-factsheet-2020-eng.pdf.

[53] Warriner, Nathan, and Kevin Bakker. The Seasonal Drivers of Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease in Thailand. University of Michigan, LSA Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, lsa.umich.edu/content/dam/urop-assets/symposium-resources/PosterExamples/LifeScience_Poster%20Example%203.pdf.

[54] Hatairat Lerdsamran, et al. “Seroprevalence of Antibodies to Enterovirus 71 and Coxsackievirus A16 among People of Various Age Groups in a Northeast Province of Thailand.” Virology Journal, vol. 15, no. 1, 16 Oct. 2018, www.researchgate.net/publication/328324106_Seroprevalence_of_antibodies_to_enterovirus_71_and_coxsackievirus_A16_among_people_of_various_age_groups_in_a_northeast_province_of_Thailand/, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-018-1074-8.

[55] Zhang, Xinglong, et al. “Hand-Foot-And-Mouth Disease-Associated Enterovirus and the Development of Multivalent HFMD Vaccines.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 24, no. 1, 22 Dec. 2022, pp. 169–169, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24010169, https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/24/1/169

[56] Chen, Xiao Jing, et al. “Japanese Encephalitis in China in the Period of 1950–2018: From Discovery to Control.” Biomedical and Environmental Sciences, vol. 34, no. 3, 1 Mar. 2021, pp. 175–183, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0895398821000362, https://doi.org/10.3967/bes2021.024, https://www.besjournal.com/en/article/doi/10.3967/bes2021.024

[57] TAGAYA, ISAMU, et al. “A LARGE-SCALE EPIDEMIC of HAND, FOOT and MOUTH DISEASE ASSOCIATED with ENTEROVIRUS 71 INFECTION in JAPAN in 1978.” Japanese Journal of Medical Science and Biology, vol. 34, no. 3, 1981, pp. 191–196, https://doi.org/10.7883/yoken1952.34.191, https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/yoken1952/34/3/34_3_191/_article

[58] TAGAYA, ISAMU, and KAZUYO TACHIBANA. “EPIDEMIC of HAND, FOOT and MOUTH DISEASE in JAPAN, 1972-1973: DIFFERENCE in EPIDEMIOLOGIC and VIROLOGIC FEATURES from the PREVIOUS ONE.” Japanese Journal of Medical Science and Biology, vol. 28, no. 4, 1975, pp. 231–234, https://doi.org/10.7883/yoken1952.28.231, https://sci-hub.se/10.7883/yoken1952.28.231

[59] Clohecy, Robert J; Conn, Rex B; Conn, Howard F. “Current Diagnosis : Clohecy, Robert J : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive.” Internet Archive, 2014, archive.org/details/currentdiagnosis00cloh/page/190/mode/2up.

[60] HALL, WILLIAM J. “Atypical Measles in Adolescents: Evaluation of Clinical and Pulmonary Function.” Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 90, no. 6, 1 June 1979, p. 882, https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-90-6-882, https://2024.sci-hub.se/6338/e546f283f03a91091f1013ce810880b6/hall1979.pdf?download=true

[61] Cherry, James D., et al. “ATYPICAL MEASLES in CHILDREN PREVIOUSLY IMMUNIZED with ATTENUATED MEASLES VIRUS VACCINES.” Pediatrics, vol. 50, no. 5, 1 Nov. 1972, pp. 712–717, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.50.5.712, https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article-abstract/50/5/712/78310/ATYPICAL-MEASLES-IN-CHILDREN-PREVIOUSLY-IMMUNIZED

[62] Fulginiti, V A et al. “Altered reactivity to measles virus. Atypical measles in children previously immunized with inactivated measles virus vaccines.” JAMA vol. 202,12 (1967): 1075-80. doi:10.1001/jama.202.12.1075, https://2024.sci-hub.se/4180/e24fbe51ed1a984fc54add5ca0ea5008/fulginiti1967.pdf

[63] Henderson, J A, and D I Hammond. “Delayed Diagnosis in Atypical Measles Syndrome.” Canadian Medical Association Journal, vol. 133, no. 3, Aug. 1985, p. 211, pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/instance/1346153, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/instance/1346153/pdf/canmedaj00266-0053.pdf

[64] Amurao, Guillermo, et al. “Vaccine Era Measles in an Adult.” Continuing Medical Education, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, vol. 66, 2000, p. 337, cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/Document/September-2017/066050337.pdf.

[65] Bligard, Carey A., and Larry E. Millikan. “Acute Exanthems in Children.” Postgraduate Medicine, vol. 79, no. 5, Apr. 1986, pp. 150–167, https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.1986.11699354, https://sci-hub.se/https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.1986.11699354

My granddaughter is heavily vaccinated aged 4 yrs. She has had X2 of these 4 in the last two years. She is always sick. Sounds correct to me. So sad her mother is totally fine to give all vaccines to her. It has to do with subsidies for childcare and the mandatory side of things in Australia also. Love your work, thankyou

I found you via Sacha. What a wonderful researcher you are! So happy to have found another voice talking truth!